Yankeetown

Project

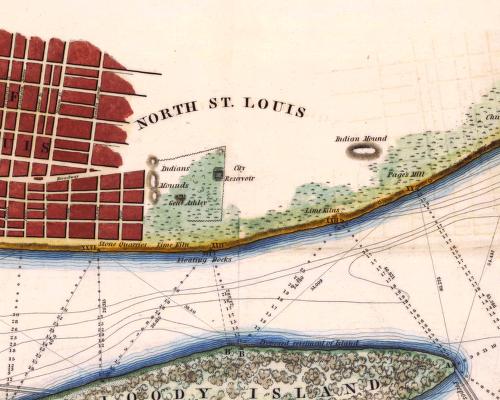

Walking into the midst of the ancient American Indian city of Cahokia in 1810, young frontier lawyer Henry Brackenridge was stunned: “I was struck with a degree of astonishment, not unlike that which is experienced in contemplating the Egyptian pyramids.” Doing the same in the 21st century is somewhat less astounding, the experience marred by modern housing, industrial alterations, a 21st century landfill, and strip development. Much has changed, but pieces of the sprawling native proto-urban complex, dating from the 11th to the 14th centuries CE, remain in our midst. We must ask questions if we are to understand its lessons.

Welcome to the Greater Cahokia website. We are engaged in a collaborative set of inquiries to understand the historical effects of this singular ancient phenomenon and its relevance for our 21st century world. Our research seeks to understand how the Cahokia that we can still see today came to be, some nine centuries ago, and how it changed the known human and nonhuman world of the Mississippi valley centuries ago. Four projects make up our collaborative effort: the Emerald Acropolis Project, the Richland Analysis Project, the Mississippian Initiative, and the Yankeetown Project. All are pieces of a larger puzzle of the rise and fall of greater Cahokia, its ancestral settlements, religious shrines, related support colonies, and later towns of descendants, often called the “Mississippians” by archaeologists, that dot the lower Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

Welcome to the Greater Cahokia website. We are engaged in a collaborative set of inquiries to understand the historical effects of this singular ancient phenomenon and its relevance for our 21st century world. Our research seeks to understand how the Cahokia that we can still see today came to be, some nine centuries ago, and how it changed the known human and nonhuman world of the Mississippi valley centuries ago. Four projects make up our collaborative effort: the Emerald Acropolis Project, the Richland Analysis Project, the Mississippian Initiative, and the Yankeetown Project. All are pieces of a larger puzzle of the rise and fall of greater Cahokia, its ancestral settlements, religious shrines, related support colonies, and later towns of descendants, often called the “Mississippians” by archaeologists, that dot the lower Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

In the 1990s, Principal Investigators Timothy Pauketat and Susan Alt began work in the Richland Complex, a Cahokia-related farming district in the upland hills east of Cahokia proper. Then, as now, the remains of the living and farming sites of people long past were under serious threat of destruction. Many were lost; more continue to be destroyed. Funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation, our crews of students and volunteers excavated large portions of Cahokia-related farming settlements, a ritual-administrative complex, and a shrine complex. More recently, Alt has sought to understand the foundational roles of the so-called Yankeetown people of southern Indiana while Pauketat turned to western Wisconsin, where Cahokians are now thought to have established a colony around one or more northern shrine complexes.

In the 1990s, Principal Investigators Timothy Pauketat and Susan Alt began work in the Richland Complex, a Cahokia-related farming district in the upland hills east of Cahokia proper. Then, as now, the remains of the living and farming sites of people long past were under serious threat of destruction. Many were lost; more continue to be destroyed. Funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation, our crews of students and volunteers excavated large portions of Cahokia-related farming settlements, a ritual-administrative complex, and a shrine complex. More recently, Alt has sought to understand the foundational roles of the so-called Yankeetown people of southern Indiana while Pauketat turned to western Wisconsin, where Cahokians are now thought to have established a colony around one or more northern shrine complexes.

Most recently, both Alt and Pauketat have teamed up for two new projects. The first involves bringing the insights of Cahokia’s rich farmlands to light, with the support of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Co-PIs Thomas Emerson and Laura Kozuch of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, join them in this collaborative effort to understand how new agrarian relationships linked farmlands and farmers with other forces of the world in ways that underwrote Cahokia’s urbanism. The second involves Pauketat and Alt’s joint effort to rethink the relationships between religion and urbanism via major new excavations at the Emerald Acropolis, with the support of the John Templeton Foundation. We hope that these projects will enable all of us to consider or reconsider the causes and consequences of Cahokia as a place and as a historical phenomenon that profounded affected the histories of many native descendant communities in the Midwest, Southeast, and Great Plains today.

The possible reasons for the emergence of Cahokia, or any early city, have intrigued scholars for more than a century. Archaeologists in North America, unfortunately, often narrowly appraise the causes, looking just to climate change or societal problems in need of a solution, without thinking about the aspirations, designs, and ingenuity of people. They also often forget to put a single place, such as the city of Cahokia, into its wider context. No cities ever developed in a vacuum. Rather, they arise in conjunction with hinterlands, immigrant communities, and mysterious far-off realms the powers of which help in some ways to define the centers, to give them power. We want to understand those relationships, and so we consider contemporary native perspectives and explanations, alongside newer theories of religion and urbanism. We seek to understand how people, places, things, and phenomena seen and unseen on the land and in the sky combined to build Cahokia and make North American history. It matters, for instance, that religion for Cahokians was probably not a conservative set of restrictive institutions but an enabling way of relating to the world around them. At Cahokia and elsewhere around the world, religious sensibilities, second-nature understandings of otherworldly powers, routinely underwrite social life such that both ordinary and extraordinary people, places, and things all mediated the fundamental relationships between life and death, day and night, past and future, and heaven and earth. Human and non-human beings and forces are all entangled in the causes and effects of history.

The possible reasons for the emergence of Cahokia, or any early city, have intrigued scholars for more than a century. Archaeologists in North America, unfortunately, often narrowly appraise the causes, looking just to climate change or societal problems in need of a solution, without thinking about the aspirations, designs, and ingenuity of people. They also often forget to put a single place, such as the city of Cahokia, into its wider context. No cities ever developed in a vacuum. Rather, they arise in conjunction with hinterlands, immigrant communities, and mysterious far-off realms the powers of which help in some ways to define the centers, to give them power. We want to understand those relationships, and so we consider contemporary native perspectives and explanations, alongside newer theories of religion and urbanism. We seek to understand how people, places, things, and phenomena seen and unseen on the land and in the sky combined to build Cahokia and make North American history. It matters, for instance, that religion for Cahokians was probably not a conservative set of restrictive institutions but an enabling way of relating to the world around them. At Cahokia and elsewhere around the world, religious sensibilities, second-nature understandings of otherworldly powers, routinely underwrite social life such that both ordinary and extraordinary people, places, and things all mediated the fundamental relationships between life and death, day and night, past and future, and heaven and earth. Human and non-human beings and forces are all entangled in the causes and effects of history.

In the relational terms above, early urbanism could not happen simply as a consequence of political or economic stimuli. Otherworldly powers that tapped people’s fundamental (ontological) predispositions, when entangled by phenomena or through experiences at places, caused cities to arise. So it was, for instance, with Rome and Mexico City, which were founded through augury, or Baghdad, established through consultations with the stars, or Amarna, home to the sun and the heretic Pharaoh Akhenaten in New Kingdom Egypt. Cahokia too was a cosmic city, a place where the moon, sun, and Milky Way touched the earth and its people. Special “shrine complexes” surrounded the city, as close as the Emerald Acropolis 24 km to the east and as far as Trempealeau, 900 river kilometers to the north in western Wisconsin. People drawn to these Cahokian places from far and wide, including the Yankeetown farmers of the Wabash and Ohio valleys to the east. Many stayed. Nine hundred years ago, people would visit them and then return home with new understandings of themselves and the great beyond.